by Tom Bill

UK Prime Minister Theresa May has stated that tackling the country’s “housing deficit” is one of her priorities.

The issue of affordability caused by a shortage of homes is most acutely felt in London. Developers and housebuilders in the capital are likely to look for positive action on measures aimed at boosting construction volumes in the government’s first post-referendum Autumn Statement on 23 November.

Recent reforms to stamp duty have had a sizable impact on demand and transactions and understanding this impact is important to inform future policy direction.

A fully-functioning London housing market is an important building block for a stronger economy, particularly in view of the economic and political uncertainty brought by the UK’s vote to leave the European Union.

The importance of the prime London housing market in particular is underlined by the fact 11% of all stamp duty revenue in England and Wales is collected in the two London boroughs of Kensington & Chelsea and Westminster.

Furthermore, housing transactions play a key role in sparking wider economic activity and encouraging social mobility. Any knock-on benefits will be reduced if housing market activity in central London is curtailed.

Our latest analysis shows the government increasingly relies on London for its stamp duty revenue, an overall figure that now exceeds £6 billion a year. However, while London’s contribution rose to 44.6% in the year to March 2016 from 41.5% a year earlier, London only accounted for 12.3% of transactions, down from 12.7%.

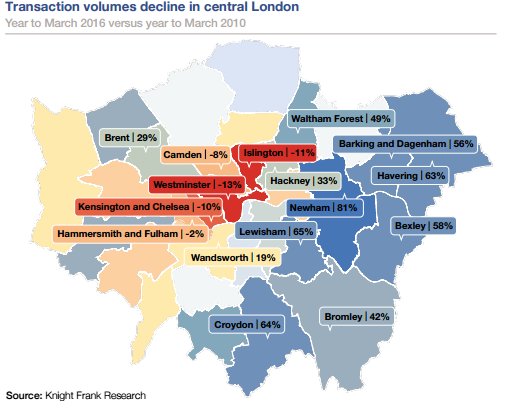

The picture emerging is one of growing fiscal reliance on areas where transactions are shrinking at the steepest rate. There are also signs the stamp duty changes introduced by former Chancellor George Osborne are disrupting the natural cycle of the London property market.

Since 1995, rising transactions in central London have typically been followed by declines as activity and house price growth spreads to outer boroughs in a trend known as the ‘ripple effect’. Following a two-to-three year period, this movement has typically reversed as central London prices become more attractive relative to outer London.

However, there are few signs of transactions increasing in central London following a broad decline in volumes that began several years ago, as the chart above shows. Transactions in Westminster, Camden, Islington, Hammersmith & Fulham and Kensington & Chelsea all fell by an average of more than 5% per year over the five year period to March 2016 versus the London average.

It is the first time this magnitude of decline has been registered in this many London boroughs since Land Registry records began in 1995. If the pattern persists, the risk is that demand and property prices in outer boroughs will become further inflated and more susceptible to future price instability.